wxWidgets: The Friendly Gateway to Linux Desktop Development

Table of Contents

Someone left a comment on one of my wxWidgets videos saying they'd spent a week trying to figure out GTK and gtkmm, and after watching the video they got further in a few hours than in that entire week. This is not uncommon, and it has a lot to do with how GTK is designed.

GTK is written in C, but it implements a heavily object-oriented framework on top of it using the GObject type system. The GObject documentation explains why:

C programmers are likely to be puzzled at the complexity of the features exposed in the following chapters if they forget that the GType/GObject library was not only designed to offer OO-like features to C programmers but also transparent cross-language interoperability.

(Source: GObject Type System Concepts)

This design makes it easy to create bindings for higher-level

languages like Python and JavaScript. But for C and C++ developers,

it adds a lot of complexity. gtkmm, the official C++ binding,

helps with some of this, but it still inherits the XML-based UI

files, the signal system, and the overall conceptual weight of GTK.

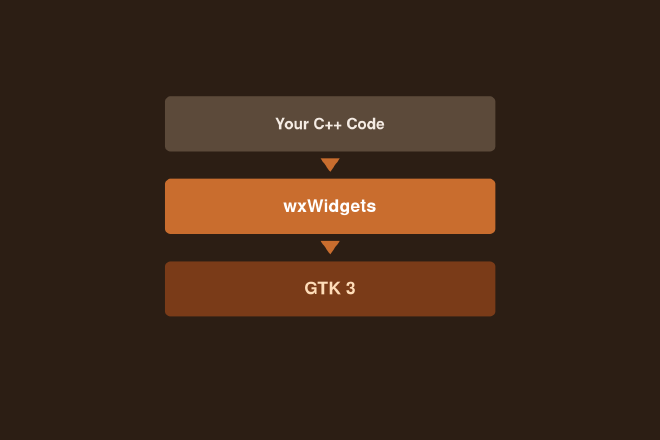

wxWidgets takes a different approach. It wraps GTK 3 on Linux (and uses native APIs on Windows and macOS), providing a straightforward C++ API. In this article, we'll implement the same simple app in all three approaches – GTK 3 in C, gtkmm, and wxWidgets – to compare the developer experience.

GTK 3 in C

We want a window with a label and a button that shows a message

dialog when clicked. The standard approach in GTK is to define the

layout in an XML file and load it with GtkBuilder.

Here's the UI definition:

<!-- ui/window.ui -->

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<interface>

<requires lib="gtk+" version="3.24"/>

<object class="GtkWindow" id="main_window">

<property name="title">GTK 3 Example</property>

<property name="default-width">400</property>

<property name="default-height">300</property>

<signal name="destroy" handler="gtk_main_quit"/>

<child>

<object class="GtkBox" id="main_box">

<property name="orientation">vertical</property>

<property name="spacing">10</property>

<property name="border-width">20</property>

<child>

<object class="GtkLabel" id="main_label">

<property name="label">Welcome to GTK 3</property>

<property name="vexpand">True</property>

</object>

</child>

<child>

<object class="GtkButton" id="click_button">

<property name="label">Click Me</property>

<signal name="clicked" handler="on_button_clicked"/>

</object>

</child>

</object>

</child>

</object>

</interface>And the C code that loads it:

#include <gtk/gtk.h>

void on_button_clicked(GtkWidget *widget, gpointer data)

{

GtkWidget *window = GTK_WIDGET(data);

GtkWidget *dialog = gtk_message_dialog_new(

GTK_WINDOW(window),

GTK_DIALOG_DESTROY_WITH_PARENT,

GTK_MESSAGE_INFO,

GTK_BUTTONS_OK,

"Hello from GTK 3!");

gtk_dialog_run(GTK_DIALOG(dialog));

gtk_widget_destroy(dialog);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

gtk_init(&argc, &argv);

GtkBuilder *builder = gtk_builder_new_from_file("ui/window.ui");

GtkWidget *window = GTK_WIDGET(

gtk_builder_get_object(builder, "main_window"));

GtkWidget *button = GTK_WIDGET(

gtk_builder_get_object(builder, "click_button"));

g_signal_connect(button, "clicked",

G_CALLBACK(on_button_clicked), window);

g_signal_connect(window, "destroy",

G_CALLBACK(gtk_main_quit), NULL);

gtk_widget_show_all(window);

g_object_unref(builder);

gtk_main();

return 0;

}We end up with two files for a label and a button. The XML uses a

nested structure of <object>, <property>, and <child> tags.

In the C code, widgets are looked up by string IDs

("main_window", "click_button"), cast through macros

(GTK_WIDGET, GTK_WINDOW, GTK_DIALOG), and signals are

connected using string names with gpointer callbacks. A typo in

a signal name or widget ID won't produce a compiler error – it

will just silently fail at runtime.

gtkmm (C++)

Let's try the C++ way with gtkmm. We can reuse the same XML

file and load it with Gtk::Builder:

#include <gtkmm.h>

#include <iostream>

class MyWindow : public Gtk::Window

{

public:

MyWindow(BaseObjectType *cobject,

const Glib::RefPtr<Gtk::Builder> &builder)

: Gtk::Window(cobject), m_builder(builder)

{

m_builder->get_widget("click_button", m_button);

m_builder->get_widget("main_label", m_label);

if (m_button)

{

m_button->signal_clicked().connect(

sigc::mem_fun(*this, &MyWindow::on_button_clicked));

}

show_all_children();

}

protected:

void on_button_clicked()

{

Gtk::MessageDialog dialog(*this, "Hello from gtkmm!");

dialog.set_secondary_text("This is a message dialog.");

dialog.run();

}

Glib::RefPtr<Gtk::Builder> m_builder;

Gtk::Button *m_button = nullptr;

Gtk::Label *m_label = nullptr;

};

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

auto app = Gtk::Application::create(argc, argv,

"org.example.gtkmm");

auto builder = Gtk::Builder::create_from_file("ui/window.ui");

MyWindow *window = nullptr;

builder->get_widget_derived("main_window", window);

if (window)

{

app->run(*window);

}

delete window;

return 0;

}We now have real classes and type-safe signal connections via

sigc::mem_fun. No more macro casts. But notice the constructor

signature – that BaseObjectType *cobject parameter is a

requirement from the GObject system. We still look up widgets by

string IDs with get_widget, and the sigc library for signal

handling takes some getting used to.

The XML file is the same nested hierarchy. For our small example it's already over 20 lines. For a real application with toolbars, menus, and dialogs, these files get large. The Glade UI designer helps with generating them, but debugging layout issues often means reading through the raw XML.

wxWidgets

Now the same thing with wxWidgets:

#include <wx/wx.h>

class MyApp : public wxApp

{

public:

virtual bool OnInit();

};

class MyFrame : public wxFrame

{

public:

MyFrame()

: wxFrame(nullptr, wxID_ANY, "wxWidgets Example",

wxDefaultPosition, wxDefaultSize)

{

auto sizer = new wxBoxSizer(wxVERTICAL);

auto label = new wxStaticText(this, wxID_ANY, "Welcome to wxWidgets");

sizer->Add(label, 1, wxALIGN_CENTER | wxALL, 20);

auto button = new wxButton(this, wxID_ANY, "Click Me");

sizer->Add(button, 0, wxALIGN_CENTER | wxBOTTOM, 20);

button->Bind(wxEVT_BUTTON, [this](wxCommandEvent &event)

{

wxMessageBox("Hello from wxWidgets!",

"Message",

wxOK | wxICON_INFORMATION);

});

this->SetSizerAndFit(sizer);

}

};

wxIMPLEMENT_APP(MyApp);

bool MyApp::OnInit()

{

auto frame = new MyFrame();

frame->Show(true);

return true;

}Event handling is a lambda passed to Bind. Layout is done in

code with sizers (see my layout basics tutorial for more on

this). No XML files, no signal library, no macro casts. It reads

like standard C++.

Also, wxWidgets uses its own reference counting mechanism. We create

out controls with the new operator, but never delete them. The parent

control (or the Application object itself, in the case of main

wxFrame) will automatically delete its children on application exit.

On Linux, wxWidgets uses GTK under the hood. Your app renders with real GTK widgets – it's not drawing its own controls. You get native look and feel with a simpler API.

Event Handling Comparison

Let's compare how each approach handles a common task: updating a label in real time as the user types into a text field.

GTK 3 (C)

static void on_text_changed(GtkEditable *editable, gpointer data)

{

const gchar *text = gtk_entry_get_text(GTK_ENTRY(editable));

gtk_label_set_text(GTK_LABEL(data), text);

}

// In setup code:

GtkWidget *entry = gtk_entry_new();

GtkWidget *label = gtk_label_new("");

g_signal_connect(entry, "changed", G_CALLBACK(on_text_changed), label);Signal names are strings, the callback takes a gpointer that

needs to be cast manually, and the label is passed as a raw

pointer through the data parameter.

gtkmm (C++)

m_entry.signal_changed().connect([this]()

{

m_label.set_text(m_entry.get_text());

});Type-safe and concise. But you need to learn the sigc signal

system, and the signal names follow GTK conventions.

wxWidgets

textCtrl->Bind(wxEVT_TEXT, [label](wxCommandEvent &event)

{

label->SetLabel(event.GetString());

});Standard C++ lambda. The event object carries the data.

Multiplatform Support

The wxWidgets code above works on Windows and macOS too, without changes. On each platform, wxWidgets uses the native toolkit:

- Linux: GTK 3

- Windows: Win32 API

- macOS: Cocoa

Your controls look native on each platform. The same source code, the same CMake build system, native appearance everywhere. If you're a Linux developer who needs to support users on Windows or Mac, you don't have to rewrite anything.

When to Use GTK Directly

GTK is the right choice if you're building something deeply integrated with the GNOME desktop, such as apps that use GIO/GVfs or need to follow the GNOME HIG closely. It's also necessary if you need GTK 4 features like the GPU-accelerated rendering pipeline, or advanced Wayland support.

For general-purpose desktop applications in C++, especially ones that need to run on multiple platforms, wxWidgets is just simpler.

Getting Started

Most Linux distributions ship wxWidgets development packages.

Ubuntu / Debian

sudo apt install libwxgtk3.2-dev build-essential cmakeOn older Ubuntu versions (20.04 and earlier), the package may be

named libwxgtk3.0-gtk3-dev instead.

Fedora

sudo dnf install wxGTK3-devel gcc-c++ cmakeArch Linux

sudo pacman -S wxwidgets-gtk3 base-devel cmakeOnce installed, your CMakeLists.txt just needs a find_package

call to pick up the system wxWidgets. If you prefer to have CMake

download and build wxWidgets automatically, you can use CMake's

FetchContent – I have a

dedicated video tutorial that walks through the setup.

Either way, the next step is to configure and build the project:

cmake -S. -Bbuild

cmake --build buildSummary

wxWidgets provides a clean C++ API over GTK 3 on Linux, with native rendering and no XML layout files. Event handling uses standard lambdas, and the same code compiles on Windows and macOS using native toolkits. If you're looking for a straightforward way to build desktop applications in C++, it's a good starting point.

Thanks for reading!